Ladakh is a good place to get an understanding of the

Tibetan problem, for Ladakh is also a part of Tibet; there is one

important difference: we never hear any bad news from Ladakh, though

their situation is quite similar. Israel Shamir looks at Tibet over the

border:

Buddha’s

Nativity in Ladakh

By Israel Shamir

Long

snake quickly moved down the mountain: hundreds of monks ran along a

curving paved path from the monastery at the top to the broad polo

grounds at the bottom, where the whole population of Leh had gathered to

celebrate the Buddha’s Nativity. Powerful, muscular monks in yellow hats

and orange robes were accompanied by peasants, city folk, urchins of

sorts, cars and cattle [on the upper photo: a Ladakh monastery on the

top, second photo: the monks]. The polo grounds with flags and

garlands, important folk sitting up on a long elevated tribune, and

performers queuing up recalled a typical May Day celebration in a

provincial Soviet town, though there were Lamas instead of Party

officials. Actually, (ex-Soviet) Tajikistan is not far from here – just

over the impassable mountains, for Leh, the capital city of Ladakh, is

located in the upper reaches of the Indus River, between the Himalayas

and the Hindu Kush, squeezed between Tibet and Kashmir, bordering on

China and Pakistan, next to Afghanistan and Tajikistan. The local people

are fond of horseback riding, so the game of polo is not a foreign

invention to them, but rather a native game. Actually, the Brits learned

it in the southern slopes of the Himalayas, and later on built polo

grounds all over the Empire.

Long

snake quickly moved down the mountain: hundreds of monks ran along a

curving paved path from the monastery at the top to the broad polo

grounds at the bottom, where the whole population of Leh had gathered to

celebrate the Buddha’s Nativity. Powerful, muscular monks in yellow hats

and orange robes were accompanied by peasants, city folk, urchins of

sorts, cars and cattle [on the upper photo: a Ladakh monastery on the

top, second photo: the monks]. The polo grounds with flags and

garlands, important folk sitting up on a long elevated tribune, and

performers queuing up recalled a typical May Day celebration in a

provincial Soviet town, though there were Lamas instead of Party

officials. Actually, (ex-Soviet) Tajikistan is not far from here – just

over the impassable mountains, for Leh, the capital city of Ladakh, is

located in the upper reaches of the Indus River, between the Himalayas

and the Hindu Kush, squeezed between Tibet and Kashmir, bordering on

China and Pakistan, next to Afghanistan and Tajikistan. The local people

are fond of horseback riding, so the game of polo is not a foreign

invention to them, but rather a native game. Actually, the Brits learned

it in the southern slopes of the Himalayas, and later on built polo

grounds all over the Empire.

Once, Leh was an important place on an important

road, but that was long time ago. Nowadays, Ladakh belongs to India,

being part of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, its farthest-away part.

The border with China and Pakistan having been closed, Leh is isolated

by frontiers, troops, rivers and mountains. In the winter, Ladakh is

practically cut off from the rest of the world. The road from Kashmir to

Ladakh was opened in May, and it will be closed again at the end of

September. It passes through awe-inspiring passes with romantic names:

Zoji-la, Namika-la, Fatu-la, reminiscent of Shangri-la, beyond the

snow-capped mountains. It is a scary experience to come to Ladakh from

Kashmir – the Zoji-la mountain pass can frighten any atheist into saying

a prayer. There is an image of the Virgin next to that of Buddha and to

an Islamic mihrab at the top of the pass, and all of them are well

attended by grateful travellers. However, the passes on the second road

to India, the Manali road, are allegedly even worse, though one wonders

whether that is even possible.

Ladakh,

this vast, frozen and sparsely populated desert, looks like the South

Sinai, a barren land with high mountains and huge military bases,

mercifully enlivened by temples and monasteries. There are trees in a

few spots in the river valleys, but otherwise this land is bare. Ladakhi

towns are tiny and rather pleasant. They have wonderful palatial houses

with colourful frescoes on the walls. Ladakh was once ruled by its own

king, but not anymore. The royal palace has been taken over by the

government. Now the queen, the widow of the last king, lives in an

ordinary house one hour’s drive from the capital Leh.

Ladakh,

this vast, frozen and sparsely populated desert, looks like the South

Sinai, a barren land with high mountains and huge military bases,

mercifully enlivened by temples and monasteries. There are trees in a

few spots in the river valleys, but otherwise this land is bare. Ladakhi

towns are tiny and rather pleasant. They have wonderful palatial houses

with colourful frescoes on the walls. Ladakh was once ruled by its own

king, but not anymore. The royal palace has been taken over by the

government. Now the queen, the widow of the last king, lives in an

ordinary house one hour’s drive from the capital Leh.

[On the third photo, a noble Ladakh lady in her

palatial mansion].

I’ve been visiting a few monasteries in this most

remote Buddhist country with an average altitude of 10,000 feet. Though

religions differ, man’s need for communing with God remains a constant.

Buddhists – like Orthodox Christians – strive to achieve this perfect

union with God; they call it enlightenment while we call it

theosis or deification. Their monasteries are full of icons they

call tanka. Their night chants begin at the same time the monks

of Mt Athos start their morning prayer, and last very, very long. There

are differences, too: though we admire and venerate our spiritual

teachers, we never worship a living person like they do. There are more

photos of the Dalai Lama in the monasteries than there were portraits of

Stalin and Mao in Russia and China. To make the comparison stick, there

are also copies of his collected works in so many languages.

Once there were many monks and monasteries; huge

reliefs of the Buddha still embellish the land, as well as their mani

walls made of ritually inscribed flat stones. But the attraction of

monkhood has faded notably. I stayed in Lamayuru, one of the biggest

monasteries in Ladakh. It is a vast complex with dozens of houses and

stupas, big and small – but there was only one resident monk. I

was told that a few more were scattered throughout the area, helping

with the harvest and teaching children. In the old days, the monks

taught children in a monastery school. Now the Indian government

provides schools, so children do not have to go to monasteries, though

monks still teach. Still, the

literacy rate here is below 25%, while in neighbouring Tibet it is

95%. Moreover, Tibet is accessible all year round even by train, while

Ladakh is not.

Ladakh is a good place to get an understanding of the

Tibetan problem, for Ladakh is also a part of Tibet, and the native

population is kin to the Tibetans. Ladakhis and Tibetans understand each

other almost as well as people from different parts of Ladakh understand

each other.

There is one important difference: we never hear any

bad news from Ladakh, though their situation is quite similar. Both are

not independent. While Tibet belongs to China, Ladakh belongs to India.

Whereas in Tibet, money and business is mainly in Chinese hands, in

Ladakh business, trade, hotels, tourism are in Indian, mainly Kashmiri

hands. The reasons for the differential treatment lie elsewhere: India

is more compliant with the West than China, and that is why China is

attacked. If India were to become equally ‘stubborn’, we should soon be

hearing about mistreated Ladakhis, too.

The people of Ladakh and of Tibet surely have their

problems but these problems are mainly due to “progress” – the State

(China or India) took over the role once performed by the monasteries.

Nowadays, roads are repaired, schools run, and taxes collected by the

state, not by monasteries. The monasteries have lost their position as

feudal seigniors. Naturally the monks are not happy about it; but the

same can be said in France or Russia: even there, the monks would like

to revert to less hectic times. Tibet is just the only place that the

Western media brings us the opinion of the monks as a valid one rather

than as curiosity.

The native people haven’t sufficient capital,

connections or experience to compete with the Indians and the Chinese in

trade and business. Native culture is being eroded by globalisation both

in Tibet and in Ladakh (as it is in your home town), but only in Tibet

we hear it called “cultural genocide”.

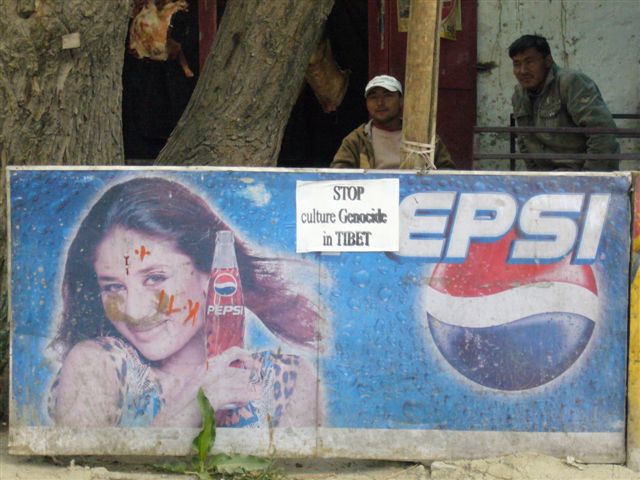

On a wall in Ladakh I spotted this sticker attached

to … Pepsi Cola sign, apparently the very opposite to “cultural

genocide”. Indeed the present attack on China because of its “cultural

genocide” in Tibet is a cynical media manipulation. Tibetans actually do

better in Tibet than Ladakhis in Ladakh, and with departure of

communism, even this reason evaporated. Communism is/was a different

religion, competing with Lamaist Buddhism of Tibetans, now they will

have to compete with Liberal Consumerism, most godless creed of our

days, equally active in Tibet, Ladakh and New York.

If ever Tibet will become independent, it is likely

to tear away the Indian territories of Ladakh and Himachal Pradesh, as

the native population is akin to Tibetans, and connected to Tibet by

blood, marriages, customs, language and religion. This is a strong

argument against giving too much support to the Tibetan cause: changes

of status quo are bloody and violent and usually are connected with

ethnic cleansing.

The Tibetans in Himachal Pradesh and Ladakh describe

themselves as ‘refugees’, but after all they live in close proximity to

their old homes, among their cousins and at their own choice. They are

as much refugees as the Irish in Liverpool. They should make their

choice: go back to Tibet or become naturalised in India. Apparently both

possibilities are open to them. Chinese Tibet is not some dreadful place

of communist torture chambers, and they can go back without fear for

their lives. Instead, they take CIA money to despoil the walls of Leh

with their nasty anti-Chinese slogans and with their cheap propaganda in

English aimed at foreign tourists. I asked some Tibetan refugees: would

they return to Tibet? Yes, we would, they said, if the Dalai Lama would

return as well, and this is not likely to happen soon.

Tibetans are just one ethnic group among many others

living in the area. Their independence would cause other small groups

claim their independence, as it happened in the most recent case of

Georgia and Ossetia. Indeed, if Kartvelis can become independent of

Russia, why Ossetia can’t become independent of Georgia? If Tibetans may

become independent of China, why Ladakhis can’t become independent of

India? Promotion of ‘national independence’ is a deadly game, it always

was, and it is better to stop it.

Let the Tibetans and the Ladakhis worship at their

monasteries and improve their lives, let the Dalai Lama concentrate his

efforts of the real Buddhist goals, i.e. seeking Nirvana, while leaving

the dreams of full cultural (let alone political) independence where

they belong – in the Dream Kingdom.